Tuesday, July 20, 2010

African braiding continued

The history of African hair braiding

Origins of Hair Braiding

When the people of Africa were brought to the New World as slaves, they were initially confronted with a loss of identify. As they traversed the Middle Passage--or the voyage by ship from Africa to America--their heads were often shaved for sanitary reasons. But their hair grew back, and with it so did the culture.

Braids and Slavery

But it was not without improvisation. They didn't have the combs and herbal treatments traditionally used in Africa, so the slaves relied on bacon grease, butter and kerosene to clean and condition their hair.

Wrapped in Pride

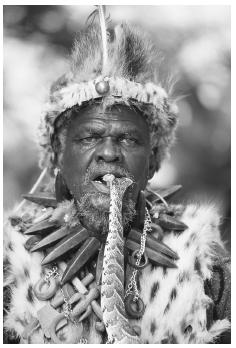

African Tribes- Ashanti people

TRIBES & PEOPLE GROUPS

ASHANTI:

The Ashanti live in central Ghana in western Africa approximately 300km. away from the coast. The Ashanti are a major ethnic group of the Akans in Ghana, a fairly new nation, barely more than 50 years old. Ghana, previously the Gold Coast, was a British colony until 1957. It is now politically separated into four main parts. Ashanti is in the center and Kumasi is the capital.

To the Ashanti, the family and the mother’s clan are most important. A child is said to inherit the father’s soul or spirit (ntoro) and from the mother a child receives flesh and blood (mogya). This relates them more closely to the mother’s clan. The Ashanti live in an extended family. The family lives in various homes or huts that are set up around a courtyard. The head of the household is usually the oldest brother that lives there. He is chosen by the elders. He is called either Father or Housefather and is obeyed by everyone.

Boys are trained by their fathers at the age of eight and nine. They are taught a skill of the fathers' choice. The father is also responsible for paying for school. Boys are taught to use the talking drums by their mothers' brother. Talking drums are used for learning the Ashanti language and spreading news and are also used in ceremonies. The talking drums are important to the Ashanti and there are very important rituals involved in them. Girls are taught cooking and housekeeping skills by their mothers. They also work the fields and bring in necessary items, such as water, for the group.

Marriage is very important to Ashanti communal life and it can be polygamous. Men may want more than one wife to express their willingness to be generous and support a large family. Women in the Ashanti culture will not marry without the consent of their parents. Many women do not meet their husbands until they are married. Even so, divorce is very rare in the Ashanti culture and it is a duty of parents on both sides to keep a marriage going.

African Foods

About African Food

Many have wondered: What do Africans eat and what does traditional African food looks like?

Many have wondered: What do Africans eat and what does traditional African food looks like?African foods are plentiful and varied. Rich in dietary fiber and often organic, they present a healthy choice when eaten in the right combination.

African food recipes are centered round a list of ingredients easily found all over the continent. These are natural unrefined food items,easily grown at subsistence farms not far away from home.

African foods are mainly starch based, with generous amount of vegetables and fresh or roasted fish or meat. This means that they are devoid of refined sugars and excess food additives and rich in bulk and fibre. Again, 90% or more of African foods are organic.

These foods are often grown behind the house at subsistence level, helped by the beautiful tropical weather, which means that different varieties of vegetables, fruits, cereals, tubers, nuts, and grains are grown all year round.

Fish, milk, meat from poultry or cow, goat, lamb, or game ("bush meat") as well as other sea foods provide their animal protein in all African communities.

Whether in the bushy savannas, typical rain forest, or coastal riverine settlements, access to such primary source of protein is not in short supply in stable traditional African setting.

There is simply no where in African you would not find farmers, hunters, herdsmen or fishermen...from Yaounde, Sapele, Lagos to Port Alexandria.

Olaudah Equiano, a.k.a Gustavus Vassa (1745 – 31 March 1797), one of the earliest black African writers in the United Kingdom, testified in his narrative, that the traditional African food is free from "refinements in cookery which debauch the taste".

Contrary to what some want the world to belief, the very balanced style of cooking seen in many African communities today has been indigenous to Africa thousands of years even before the slave trade, or even before the incursion of Arabian tradesmen into that continent.

The narrative of Olaudah Equiano (Gustavus Vassa the African), as well as the same preserved manner of cooking still seen in newly found African societies testifies to this fact.

Where ever they went, Africans took along with them their cooking. Thus today, all over the world, Africans still cook alike with some little variations.

Like their Asian counterparts, most cuisines of Africa are quite spicy, prepared with very hot chillies a common trend in most hot countries.

In the West Indies, the afro-Caribbean food is thus not a great deviation from traditional African dishes.

In North America, the African American foods are now generally referred to as soul food. Soul food was thus new to America, but not to the Africans who brought with them the ideas, despite been deprived of the proper ingredients with which to prepare these meals.

Thankfully, soul food is now very popular, and eaten all over black communities in America.

See what African food looks like in specific terms as we take a ride through the various African countries and visit their traditional food stuff in the African foodstuffsection.

The African Dinners

The typical African, whether in a rural farming community or in the bustling city milieu takes great care to see that meals are properly served and eaten. Great attention is also given to how the meals are prepared and what are its constituents.Breakfast is often a must, certainly lunches, and then dinner or supper.

We shall mention briefly here, a few food items eaten by Africans from West of the continent, for breakfast, lunch, and supper as a preview to what the African dinners look like.

African Breakfast

Breakfast is eaten before going to the farm or work place. In farming communities, breakfast is obviously so important to provide energy for the work ahead. Breakfast is often light, and could vary greatly, depending on the part of the continent as well as the culture.

In West Africa, Breakfast food items would include:

- Kunu or millet porridge in Northern Nigeria

- Ogi or maize pap (also called akamu) served with akara also called beans cake in Southern, Western and Eastern Nigeria

- Boiled Yam and plantain, served with fresh fish pepper soup.

Lunch

Lunch is eaten at any time from mid day to 4pm. It is often the heaviest meal of the day. Lunch in Africa is easily prepared from any of the main staples including:

- Cassava products like Gari akpu or starch (usin served with vegetable soup or banga soup or egusi soup or Ofe Onubu.

- Pounded yam or semolina or ground rice (tuwo shinkafa) or corn meal (tuwo masara) or amala made from elubo served with any of the above soups orewedu or abula or gbegiri soup in the south of Nigeria, or Miyan kuka or Miyan kabewa.

- Jollof rice served with moimoi and fried plantain (see picture above).

Supper or Dinner

Supper is eaten any time from 5pm to 10pm in Africa.

It is often a light meal, but can also be a selection of any of the above meals eaten for lunch.

For a full overview of what is eaten at various times and in different parts of the continent, see sections on the respective type of food, or see our recipe section.

If you have never eaten or tried an item of African food before, go for it. It is delicious, refreshing, though could be quite spicy, and certainly nutritious.

Comments about African foods? post them below. You can also post list of African food items eaten in your region, if you did not find it mentioned here.

African Religions: Death and Dying

In the religions of Africa, life does not end with death, but continues in another realm. The concepts of "life" and "death" are not mutually exclusive concepts, and there are no clear dividing lines between them. Human existence is a dynamic process involving the increase or decrease of "power" or "life force," of "living" and "dying," and there are different levels of life and death. Many African languages express the fact that things are not going well, such as when there is sickness, in the words "we are living a little," meaning that the level of life is very low. The African religions scholar Placide Tempels describes every misfortune that Africans encounter as "a diminution of vital force." Illness and death result from some outside agent, a person, thing, or circumstance that weakens people because the agent contains a greater life force. Death does not alter or end the life or the personality of an individual, but only causes a change in its conditions. This is expressed in the concept of "ancestors," people who have died but who continue to "live" in the community and communicate with their families.

This entry traces those ideas that are, or have been, approximately similar across sub-Saharan Africa. The concepts described within in many cases have been altered in the twentieth century through the widespread influence of Christianity or Islam, and some of the customs relating to burials are disappearing. Nevertheless, many religious concepts and practices continue to persist.

The African Concept of Death

Death, although a dreaded event, is perceived as the beginning of a person's deeper relationship with all of creation, the complementing of life and the beginning of the communication between the visible and the invisible worlds. The goal of life is to become an ancestor after death. This is why every person who dies must be given a "correct" funeral, supported by a number of religious ceremonies. If this is not done, the dead person may become a wandering ghost, unable to "live" properly after death and therefore a danger to those who remain alive. It might be argued that "proper" death rites are more a guarantee of protection for the living than to secure a safe passage for the dying. There is ambivalence about attitudes to the recent dead, which fluctuate between love and respect on the one hand and dread and despair on the other, particularly because it is believed that the dead have power over the living.

Many African peoples have a custom of removing a dead body through a hole in the wall of a house, and not through the door. The reason for this seems to be that this will make it difficult (or even impossible) for the dead person to remember the way back to the living, as the hole in the wall is immediately closed. Sometimes the corpse is removed feet first, symbolically pointing away from the former place of residence. A zigzag path may be taken to the burial site, or thorns strewn along the way, or a barrier erected at the grave itself because the dead are also believed to strengthen the living. Many other peoples take special pains to ensure that the dead are easily able to return to their homes, and some people are even buried under or next to their homes.

Many people believe that death is the loss of a soul, or souls. Although there is recognition of the difference between the physical person that is buried and the nonphysical person who lives on, this must not be confused with a Western dualism that separates "physical" from "spiritual." When a person dies, there is not some "part" of that person that lives on—it is the whole person who continues to live in the spirit world, receiving a new body identical to the earthly body, but with enhanced powers to move about as an ancestor. The death of children is regarded as a particularly grievous evil event, and many peoples give special names to their children to try to ward off the reoccurrence of untimely death.

There are many different ideas about the "place" the departed go to, a "land" which in most cases seems to be a replica of this world. For some it is under the earth, in groves, near or in the homes of earthly families, or on the other side of a deep river. In most cases it is an extension of what is known at present, although for some peoples it is a much better place without pain or hunger. The Kenyan scholar John Mbiti writes that a belief in the continuation of life after death for African peoples "does not constitute a hope for a future and better life. To live here and now is the most important concern of African religious activities and beliefs. . . . Even life in the hereafter is conceived in materialistic and physical terms. There is neither paradise to be hoped for nor hell to be feared in the hereafter" (Mbiti 1969, pp. 4–5).

The African Concept of the Afterlife

Nearly all African peoples have a belief in a singular supreme being, the creator of the earth. Although the dead are believed to be somehow nearer to the supreme being than the living, the original state of bliss in the distant past expressed in creation myths is not restored in the afterlife. The separation between the supreme being and humankind remains unavoidable and natural in the place of the departed, even though the dead are able to rest there and be safe. Most African peoples believe that rewards and punishments come to people in this life and not in the hereafter. In the land of the departed, what happens there happens automatically, irrespective of a person's earthly behavior, provided the correct burial rites have been observed. But if a person is a wizard, a murderer, a thief, one who has broken the community code or taboos, or one who has had an unnatural death or an improper burial, then such a person may be doomed to punishment in the afterlife as a wandering ghost, and may be beaten and expelled by the ancestors or subjected to a period of torture according to the seriousness of their misdeeds, much like the Catholic concept of purgatory. Among many African peoples is the widespread belief that witches and sorcerers are not admitted to the spirit world, and therefore they are refused proper burial—sometimes their bodies are subjected to actions that would make such burial impossible, such as burning, chopping up, and feeding them to hyenas. Among the Africans, to be cut off from the community of the ancestors in death is the nearest equivalent of hell.

The concept of reincarnation is found among many peoples. Reincarnation refers to the soul of a dead person being reborn in the body of another. There is a close relationship between birth and death. African beliefs in reincarnation differ from those of major Asian religions (especially Hinduism) in a number of important ways. Hinduism is "world-renouncing," conceiving of a cycle of rebirth in a world of suffering and illusion from which people wish to escape—only by great effort—and there is a system of rewards and punishments whereby one is reborn into a higher or lower station in life (from whence the caste system arose). These ideas that view reincarnation as something to be feared and avoided are completely lacking in African religions. Instead, Africans are "world-affirming," and welcome reincarnation. The world is a light, warm, and living place to which the dead are only too glad to return from the darkness and coldness of the grave. The dead return to their communities, except for those unfortunate ones previously mentioned, and there are no limits set to the number of possible reincarnations—an ancestor may be reincarnated in more than one person at a time. Some African myths say that the number of souls and bodies is limited. It is important for Africans to discover which ancestor is reborn in a child, for this is a reason for deep thankfulness. The destiny of a community is fulfilled through both successive and simultaneous multiple reincarnations.

Transmigration (also called metempsychosis) denotes the changing of a person into an animal. The most common form of this idea relates to a witch or sorcerer who is believed to be able to transform into an animal in order to perform evil deeds. Africans also believe that people may inhabit particular animals after death, especially snakes, which are treated with great respect. Some African rulers reappear as lions. Some peoples believe that the dead will reappear in the form of the totem animal of that ethnic group, and these totems are fearsome (such as lions, leopards, or crocodiles). They symbolize the terrible punishments the dead can inflict if the moral values of the community are not upheld.

Burial and Mourning Customs

Death in African religions is one of the last transitional stages of life requiring passage rites, and this too takes a long time to complete. The deceased must be "detached" from the living and make as smooth a transition to the next life as possible

Many African burial rites begin with the sending away of the departed with a request that they do not bring trouble to the living, and they end with a plea for the strengthening of life on the earth and all that favors it. According to the Tanzanian theologian Laurenti Magesa, funeral rites simultaneously mourn for the dead and celebrate life in all its abundance. Funerals are a time for the community to be in solidarity and to regain its identity. In some communities this may include dancing and merriment for all but the immediate family

Read more: African Religions - rituals, world, burial, body, funeral, life, customs, beliefs, time, person, human, The African Concept of Death http://www.deathreference.com/A-Bi/African-Religions.html#ixzz0uGu9JSo2

African Studies Give Women Hope in HIV Fight

After nearly two decades of research the efforts for an effective measure to control the HIV epidemic may be near. Researchers have found a microbicide to block the transmission of HIV. This product is being tested in the rural and urban areas of South Africa. The vaginal microbicidal gel cotains antiretroviral medication that is used to treat HIV and Aids with a success rate of about 40%.

After nearly two decades of research the efforts for an effective measure to control the HIV epidemic may be near. Researchers have found a microbicide to block the transmission of HIV. This product is being tested in the rural and urban areas of South Africa. The vaginal microbicidal gel cotains antiretroviral medication that is used to treat HIV and Aids with a success rate of about 40%.This process is still being researched for actuall effectiveness and may be years before it will become public, but if produced in a large enough scale the cost of the gel would only be 25cents per application. Not only will it be cost effective but it will be controllable by the women and young girls in South africa.

Its not a measure to treat pre existing HIV and Aids cases but its a look into how to prevent new cases from comming into existence. This will decrease the infant mortality rate significantly if women use the micrbicidal gel 12 hours before coming into contact with an infected male, it also gives young girls and women a sense of control without relying on a male, something women of South Africa have a lot of.

Okaseni Village

Okaseni village has 4,299 villagers. Their casg crop is coffe they also grow bananas, maize, beans, fruits and vegetables. These products are also for selling as well as food source. The Okaseni village does not have access to health care clinics or hospitals. The nearest health care source is about 7 kilometers depending on their location throughout the village. Malariaa is the most common and deadly disease that the villagers of Okaseni is faced with, however the HIV and Aisd epidemic has been causing the most deaths recently.Poor drinking water, and toilet usage, along with lack of nutrition has increased the chances of diseases and left a lot of children in orphan situations.

Okaseni village has 4,299 villagers. Their casg crop is coffe they also grow bananas, maize, beans, fruits and vegetables. These products are also for selling as well as food source. The Okaseni village does not have access to health care clinics or hospitals. The nearest health care source is about 7 kilometers depending on their location throughout the village. Malariaa is the most common and deadly disease that the villagers of Okaseni is faced with, however the HIV and Aisd epidemic has been causing the most deaths recently.Poor drinking water, and toilet usage, along with lack of nutrition has increased the chances of diseases and left a lot of children in orphan situations.HIV in South Africa

As part of 2010 guidelines pregnant mothers who are HIV positive will receive trearment at 14weeks of pregnancy rather than at the usual 28weeks. This is because the CD4 levels may be at a lower level earlier on and can be treated before the mothers blood levels are too low to prevent the spread of the HIV virus from entering the unborn child. This positive approach moves South Africa in the same direction of the WHO recommendations and receive treatment earlier on. This program also continues treatment post pregnancy, before another pregnancy occurs.